Smell, Taste, and Covid-19: What Happens When A Wine and Food Writer Loses Two of Her Most Prized Senses

On Wednesday morning, March 18th, 2020, I waited for an hour outside Trader Joe’s; the line snaked down Amsterdam Avenue and wrapped around the corner of 92nd Street. Coronavirus cases in New York City were soaring and it was time to stock up on canned goods, frozen vegetables, rice, beans, olive oil, and enough fresh items to last at least a week. Nightly home cooked meals, complete with a bottle of wine, would surely help ease the stress of being cooped up inside a New York City apartment for days on end.

We were going to stay home and stay safe. Or so I thought.

The author with her family, Left to right: Colette, Gabrielle, Lisa, Jolie, and Joel.

Later that day, I received an email from Born Digital Wine Awards informing me that my article, Taste the Flavors of Montecucco, Tuscany’s Up-and-Coming Wine Region, was shortlisted for Best Wine Tourism Content. Although I’ve been working in wine sales since 2012, it’s only been a few years since I founded The Wine Chef, and started writing for Grape Collective. Making the cut for the award felt like a thin ray of sunshine peeking through ominous dark clouds overhead.

That evening, Joel and I and two of our daughters, Gabrielle and Jolie, were hunkered down and ready to share a celebratory bottle of Montecucco red. The wine, produced by Poggio al Gello winery, was a perfect match with spaghetti and meatballs in a rich tomato sauce. It tasted like earth, fruit, and flowers mingled together, lifted by bold tannins and a cool, bright energy. Poggio al Gello is a small, organic winery known for its revival of ancient Tuscan grape varieties. When I visited the property in 2018, owners Giorgio and Alda sent me home with a bottle of their rare Pugnitello wine. A year and a half later, one sniff of its heady aromas promised that we were in for a treat.

Although our lives would be on hold for who knows how long, we would help ease our worries by savoring a different wine each night. Lockdown wouldn’t be so bad after all. We were at home and staying safe. Or so I thought.

Coronavirus Strikes

The next day I woke up with a fever. As the day went on, the heaviness in my chest progressed to sharp pains and coughing; I came down with the chills, body aches, and a dry cough. It felt like someone with a tiny knife was running up and down my body, randomly stabbing me. At one point, there was such tightness in my chest that it felt like I was having a heart attack, relieved by lying down.

Surprisingly, I still had an appetite. My friend Nicole who during college would happily devour tubs of peanut butter ice cream with me, offered a dose of black humor: “You would find a way to eat even if you were on a ventilator,” she texted. That evening, with the aid of Tylenol, I savored a tasty dish of Asian-style salmon with sesame noodles, prepared by Gabrielle and Jolie who were still feeling well.

The following morning, I noticed I couldn't taste my toothpaste. I immediately headed to the kitchen to see if I could smell or taste anything: coffee grinds, lemons, dish soap. Nothing. I made a bowl of breakfast oatmeal. It could’ve been warm cottage cheese. What was happening? Whenever I lost the ability to taste in the past, it had been accompanied by a severe cold and my nasal passages were stuffed up. Not this time.

I tested positive for the coronavirus on March 25th. The doctor said we could assume, based on the symptoms, that Joel, Gabrielle, and Jolie had also contracted the virus (luckily, my daughter Colette stayed put in her apartment and remains healthy). While I was the hardest hit, with a fever that lasted ten days, we each had our own distinct symptoms. But all four of us lost our sense of smell and taste. We could discern sweet, spicy, bitter, and salty notes, but none of a food’s particular flavor. During meals, we would half-jokingly say to each other, “great texture!” After a few days, it wasn’t so funny. Needless to say, a bottle of wine was not a part of the equation anymore.

Losing Your Sense of Smell and Taste

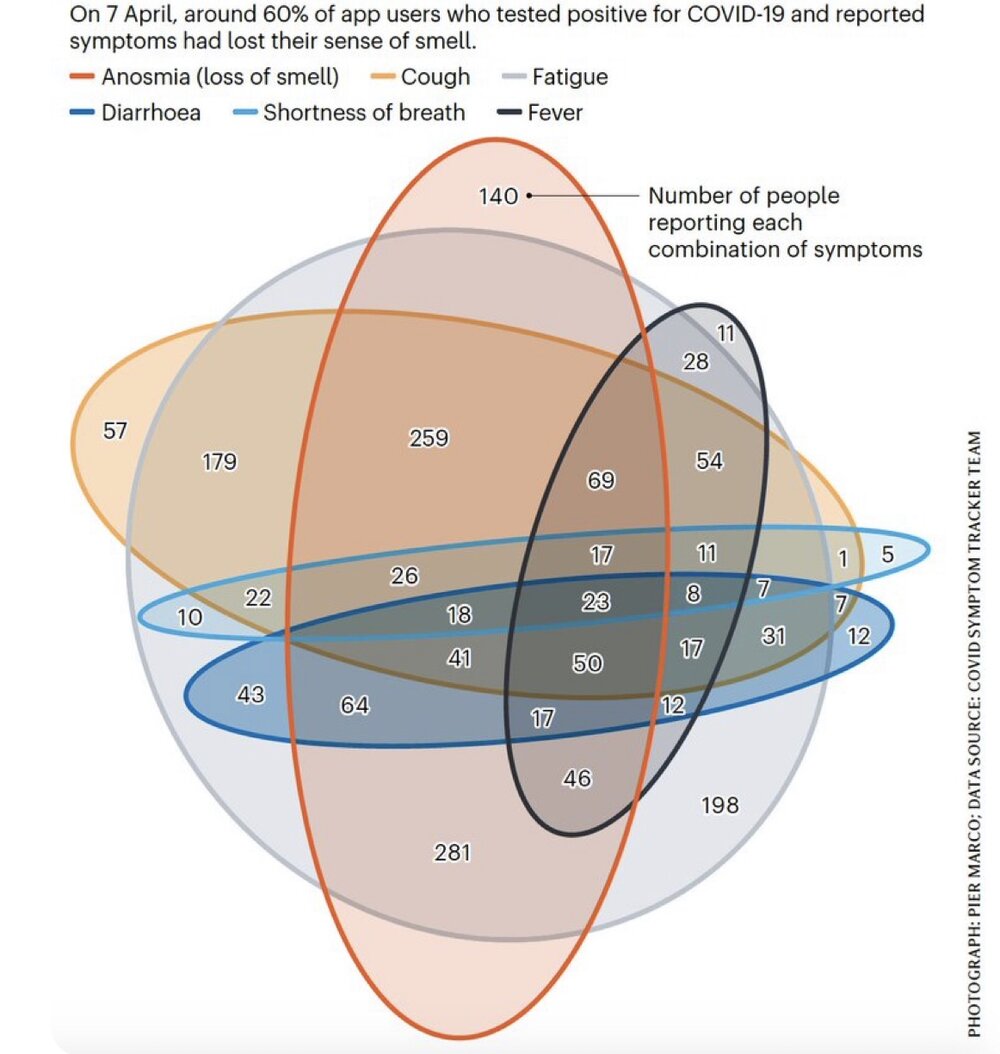

If you’ve never lost your sense of smell (anosmia), it may be hard to understand why it’s so devastating. According to The Anosmia Foundation, over two million Americans suffer from a loss of smell, and subsequently taste, often due to head injuries, but also from contracting a virus. The CDC now lists anosmia as common in many coronavirus patients with evidence that the virus affects delicate smell receptors.

In an article published in BBC news, Professor Barry C Smith, founder of The Centre for the Study of the Senses, states that more of our brain, memory, and tastes are controlled by scents. He laments that smell is an underrated sense. “Studies have shown that people who lose their sense of smell end up more severely depressed than people who go blind,” says Smith. He says that losing the ability to smell not only takes the enjoyment out of eating, but leads to people and places not smelling familiar anymore. “Losing that emotional quality to your life is incredibly hard to deal with,” adds Smith.

Elizabeth Zierah couldn’t agree more. In her article on Slate.com, she talks about how the loss of smell and taste can cause more severe anxiety and depression than other, more serious health issues. Zierah, who suffered a debilitating stroke at the age of 30, developed anosmia a few years later. “Without hesitation,” she says, “losing my sense of smell has been more traumatic than adapting to the disabling effects of the stroke.”

As someone who has always taken great pleasure in eating and drinking, I began thinking about how I would deal with the loss of two of my most treasured senses, smell and taste.

A Food Lover From the Get Go

When I was eight years old, Santa brought me an Easy-Bake oven. On that day, I turned into a mini chef, using the heat of a light bulb to whip up tiny treats. In middle school I graduated to the grown-ups’ oven and my weekends were spent baking: brownies, angel food cake, snickerdoodle cookies, apple crisp, and more. The buttery scent of freshly baked goods was a given at my house in those days.

As a teen, I still enjoyed baking, but it was the post-party midnight trips to Kelly’s, a fast food restaurant known for juicy roast beef sandwiches, that I craved on the weekends. In college, during breaks from pizza and ice cream, visits to my boyfriend’s home in Connecticut were also an introduction to proper French cuisine. His mother, a gourmet cook, prepared elaborate meals with fresh dill, tarragon, and rosemary from her extensive herb garden.

Two weeks after graduating college, Nicole and I moved to New York City where every type of cuisine was right there in our backyard. Every day was an opportunity to try a new cuisine — Indian, Japanese, Spanish, Moroccan, and on and on. During one three month period, we dined out on Mexican food 56 times — a decade’s worth of nachos, enchiladas, and margaritas in just a few months!

In 1989, I decided to follow my passion for food and left my advertising sales job at The New York Times to take a full-time, six-month cooking course at The French Culinary Institute. I was finally learning to cook more than baked goods and I loved showing off my new skills to family and friends. This passion for food sparked an interest in wine which eventually led to my becoming a wine writer.

A Slow Recovery

After 11 days without any smell or taste, I noticed I could finally detect a few scents — coffee grinds, orange peel, blue cheese — it was faint, but it was something. The next day I was thrilled to taste a little bit too. It had been almost two weeks since I had enjoyed a meal, and it felt like a real breakthrough. Yet, as I was soon to find out, hope can easily lead to frustration when you’re recuperating from coronavirus. Good days are often followed by bad. One day your symptoms are fading and the next day you can’t smell the coffee brewing and your fever is back.

On Jolie’s 19th day of anosmia, she broke down crying at dinner, fearing her sense of smell and taste would never fully come back. The rest of us tried to comfort her, yet deep down inside we knew we were feeling the same way.

After several days without fever, I was ready to give wine a try. With high hopes, I swirled and sniffed a glass of red Rioja. Hmmm, not much aroma. Then I tasted it. Terrible! It was just bitter, salty alcohol. I was disappointed, but promised myself that I would keep trying. By the fourth day I noticed that, while there wasn’t much aroma or taste, at least it wasn’t horrible anymore. It was just boring, as if all of its loveliness had been hidden, covered up with a blanket.

Now What?

During the days when I couldn’t smell or taste anything, I would think about what I would do if I never regained my olfactory senses. Now that they’re partially back, I wonder if I would be able to write about wine and food without completely tasting it. How would I compare a selection of Burgundy Pinot Noirs to those of Oregon? Could I talk about the latest vintage of great Bordeaux and how different it is from the year before? Could I confidently suggest wines to go with spicy Korean cuisine? The answer to those questions would be no, but writing about wine can be so much more than talking about aromas and tastes. Often, wine is the lens through which we can dig deeper into issues of climate change, sustainability, and discrimination in the workplace, for example. I could continue interviewing winemakers and writing the story behind the winery and the people who work there.

But, in all honesty, I’m not sure I could deal with the frustration of not being able to experience the nuances of flavor in a glass of wine. Just like meeting someone for the first time, that initial taste of a wine is a visceral experience — it’s all about how it makes you feel. Sometimes it’s joy and pleasure, other times boredom, or just misery and discontent. How a wine smells and tastes triggers an emotional response that motivates me to learn more, and to want to share the discovery by writing about it (or not).

To help deal with my loss, I joined Facebook’s Covid-19 Smell and Taste Loss group and every day I check in to see how others are doing. Many have recovered and most offer hope and inspiration, like Aga Ciuba, who wrote, “We will be fine. It’s improving for me day by day. Yesterday I was so happy I ate a whole bag of my favorite chocolate candies even though I could only taste max 30% of their flavor.” From the group discussions, I have learned the importance of regular “smell training” with essential oils like lemon, orange, eucalyptus, and cinnamon that can help reinvigorate the damaged olfactory nerve cells.

Every night, in addition to smelling and tasting wine, I head to my liquor cabinet, not to fix a drink, but to smell: mezcal, gin, bourbon, smoky whiskies, grappa. At this point, every little whiff of scent feels like a gift. Twice, the gin smelled aromatic enough to inspire a wonderfully citrusy and textured (there’s that word again!) gin and tonic.

Feeling Lucky and Grateful.

With the constant wailing of ambulance sirens in NYC, I’m aware that my lack of smell and taste is insignificant compared to what others are going through. I worry for those who are on ventilators, battling for their lives, and as a survivor, I soon hope to donate plasma. The doctors, nurses, and others who work in hospitals struggle daily with the constant dread of catching the virus or bringing it home to their loved ones. Yet they continue to fight for the lives of those most severely affected.

And for those who remain healthy, many are having a hard go of it, grappling with the financial and emotional effects of the virus. The loss of a job and the constant fear of catching Covid-19 is leading to financial ruin and despair.

My doctor says that she never likes to tell a patient who was sick that they were lucky. “But you are very lucky,” she told me. Her words echoed my thoughts and I feel grateful that I was able to recover comfortably in my own home, surrounded by family. There was even a silver lining in our cloud: we all had the virus so we didn’t have to isolate away from each other. In our worst states, we could read and watch movies cuddled up on the couch together. The proverb “misery loves company” was never more apt. We were able to sit together at dinner and commiserate over tasteless food about the depressing state of the world.

On a brighter note, Colette and several others brought much joy when they checked in on our daily progress. I am now feeling more energetic and can make it through a full day without napping. I am slowly detecting more nuances of flavor in my food and wine, and I remain hopeful that I will completely recover my sense of smell and taste. Who knows, perhaps this experience will enable me to discern and appreciate scents and flavors even better than before. I look forward to the day when a sniff of a wine will once again inspire me to write about it. In the meantime, I am grateful for my life and what little I can smell and taste.

The author and her family enjoying Maine lobster during better days.